Ming Dynasty (1368 ∼ 1644 AD)

About Ming Dynasty

The founder of the Ming dynasty was Zhu Yuanzhang, better known as Hongwu. He was a Han Chinese peasant and former Buddhist monk turned rebel army leader, who led the defeat of the Mongols in 1368 AD. Extensive political and agricultural reforms were undertaken by the early Ming resulting in a period that was both rich and fruitful in terms of economy, art and culture. This was especially so under the reign of the second Emperor Yongle, 1403∼24.

China was flourished under Emperor Yongle's leadership. This was a period of many firsts. The Forbidden City was constructed, dictionaries such as the Great Dictionary of the Yongle Reign (yong le da dian) were written and explorers such as Zheng He traveled the world for new ideas. Famous literary works such as the Journey to the West (xi you ji) and The Plum in a Golden Vase (jin ping mei) were written during this time. During the later period of the Ming, Western culture flooded into China. A number of Jesuits arrived bringing with them their religion, philosophies and knowledge. Matteo Ricci, the famous Italian Jesuit missionary scholar, was to develop a close relationship with Chinese scholars.

China was flourished under Emperor Yongle's leadership. This was a period of many firsts. The Forbidden City was constructed, dictionaries such as the Great Dictionary of the Yongle Reign (yong le da dian) were written and explorers such as Zheng He traveled the world for new ideas. Famous literary works such as the Journey to the West (xi you ji) and The Plum in a Golden Vase (jin ping mei) were written during this time. During the later period of the Ming, Western culture flooded into China. A number of Jesuits arrived bringing with them their religion, philosophies and knowledge. Matteo Ricci, the famous Italian Jesuit missionary scholar, was to develop a close relationship with Chinese scholars. Despite such progress, the dynasty became increasingly dictatorial and the Ming reign was to be short-lived. The Mongols once again became a threat and Japanese pirates, known as wokou, became an increasing menace. In the seventeenth century, the Manchus began to gather power over an already weakened country, and would eventually form the Qing Dynasty.

Different Schools Of Medicine

Following the Jin and Yuan dynasties, there were great debates among physicians from the different schools advocating different philosophies of Chinese medicine. The work of many eminent physicians and the publication of numerous treatises testify to the blossoming of medical theories and practices. The three major schools in this period were the school of nourishing yin, the school of warming and invigoration, and the school of febrile disease.

The school of nourishing yin was found by Zhu Zhenheng in the previous dynasty, which was aimed at nourishing yin and quenching the minister fire. Two famous doctors, Wang Lu and Dai Sigong, became disciples of this school and continued to advocate in their practice.

Although the schools of nourishing yin had their followers during the Ming dynasty, many physicians supported the idea of warming and invigoration methods founded by Li Gao. The school of warming and invigoration believed that tonifying spleen and stomach to preserve the inborn energy is an essential approach in keeping away illness. The foremost physicians in this area of thought were Xue Ji, Zhao Xianke and Zhang Jiebin.

Xue Ji (1488∼1558), whose father had been a member of the official Academy of Medicine, was a specialist in internal medicine, surgery, gynecology, pediatrics and otorhinolaryngology. He published a wide variety of medical books, including A Synopsis of Internal Medicine (nei ke zhai yao), Essentials of External Medicine (wai ke shu yao), An Elaboration of External Medicine (wai ke fa hui), A Synopsis of Women Diseases (nu ke cuo yao), A Repertory of Traumatology (zheng ti lei yao), and A Repertory of Stomatology (kou chi lei yao), and providing ample testimonies to his medical interests. He also advocated to use atractylodes rhizome, ginseng, liquorice root or astragalus root as main ingredients in remedies, which could treat poor appetite and fatigue and were able to invigorate the spleen and stomach, and replenish qi," as proposed by his predecessor, Li Gao.

Zhao Xianke further developed the teaching of Xue Ji by formulating a concept of "vital gate." According to Zhao's book, Key Link of Medicine (yi guan), it was this vital gate, located between the kidneys, rather than the heart that governed the body. The amount of "fire" generated by this gate determined the degree of available energy. Zhao believed in a relationship between fire (yang) and water (yin). Nourishment of one or the other was the basis for his treatment and to achieve this he gave his patients one of two pills: "the pill of eight ingredients" to reinvigorate fire (yang), and "the pill of six ingredients" to reinvigorate water (yin)." The prescriptions were taken from the text written by Zhang Zhongjing in the second century.

Another notable medical commentator of the time was Zhang Jiebin (1563∼1640), also known as Zhang Jingyue. He disagreed with Zhu Zhengheng that yang was generally excessive whilst yin was insufficient, believing instead that yang was the source of life and the root of our physical existence. He proposed to invigorate kidney yang and kidney yin gently, and be cautious of using herbs with cold or cool, and harsh properties. He wrote many works aimed at explaining and simplifying the ancient classic, Yellow Emperor's Classic of Internal Medicine. He also compiled a comprehensive medical book, Jing-Yue's Complete Works (jing yue quan shu), in his later life.

Breakthrough in the school of febrile disease

Prior to the Ming dynasty, febrile disease (wen bing) or cold damage (shang han) were the general names for acute feverish disease caused by exogenous pathogens. The terms covered both infectious and non-infectious diseases. It was only at the beginning of the Ming dynasty that the precise features and a definition of wen bing were formulated, wen bing then became the name for infectious disease.

Plague was a major problem during the Ming period and was spoken of as wen yi (pestilence), that is any kind of fatal epidemic disease. An outbreak in 1641 wiped out a large portion of the population in China. A physician, Wu Youxing (1580∼1660), made an important breakthrough on it. After extensive observation and research on epidemic diseases, he published a book On Pestilence (wen yi lun), which was a treatise on epidemic diseases. His concept of pestilent influences (li qi) was a fresh idea about the cause of febrile diseases, that had push forward the school of febrile disease to be established, with its own particular theory and treatment measures. In the book, he clarified and contrasted between cold damage and febrile disease, about the differences in causes, route of attacking, presentations, clinical staging, and treatment.

Smallpox is a serious contagious and fatal infectious disease, which was a great scourge of the country during the Ming dynasty. Although the disease had recorded as early as in the Han dynasty by Ge Hong, it was not until the years 1567∼72, there was documented about the prevention method. Ancient people adopted clothing method and nasal method to get the immunity against smallpox. The clothing method was to find patients who were in active stage of smallpox, and took their underwear to wear; the nasal method was to collect blister fluid from patients or dried scabs from healed patients, and put some into the nasal cavity. Since the first method had a risk of serious infection, the latter method especially the dried scabs method was more safe and effective. This was regarded as the early use of anti-smallpox vaccination.

Advancement in Surgery

Various other new medical ideas arose during the Ming. The concept that both oral and external remedies should be introduced to tackle wound problems was shared by several physicians and surgeons. It was extended to the treatment of cancer by a number of practitioners who recognized contributory causative factors, such as depression and the eating of fried, spicy or charred food. The development during the Ming of methods for achieving analgesia (pain relief), asepsis (absence of illness causing organisms) and hemostasis (the arrest of bleeding) contributed to an improvement in surgical technique.

Chen Shigong (1555∼1636) was one of the outstanding surgical figures of this time. He dedicated himself to external medicine for over 40 years. His Orthodox External Medicine (wai ke zheng zong), first published in 1617, covered a series of surgically treatable diseases and many effective proven prescriptions. The book outlined the surgical procedure for the repair of a slashed throat, the use of copper wire to excise nasal polyps under local anesthesia, and described in detail for cancer of the neck and breast. He also proposed to use both oral and surgical treatment for wound problems, he claimed that abscess should be cut open as early as possible in order to prevent further deterioration.

Another famous surgeon in the same period was Wang Kentang (1549∼1613), he wrote the Standards for Diagnosis and Treatment of Ulcers and Boils (yang yi zhengzhi zhun sheng) in 1608. It was a volume treatise on surgical diseases, in which he advocated bone physicians should have a full knowledge about skeleton structures of the body. He described many of the earliest surgeries in Chinese medicine history, such as suture surgery of a broken trachea, plastic surgeries of ears, lips, or tongue, and also emergent surgeries for traumas of the skull, shoulder, neck, chest, abdomen, lumber, hip and spine and their herbal remedies too. At that time, he already realized that tumor with a fixed location might not be cured by surgery.

Ravages of Venereal Disease

The cleanliness of the sexual habits observed by the Chinese was thwarted during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries by outbreaks of syphilis that ravaged the country. The disease appears to have spread from the southern coastal region of Canton. Physicians of the period devoted much effort to combating syphilis and two notables were Wang Ji and Chen Sicheng.

Wang Ji (1463-1539) held the view that a combination of internal and external therapy was needed to deal with venereal disease and prescribed a "decoction of the four rulers" (ginseng, large head atractylodes root, Indian bread and liquorice root) to sustain vital energy (qi), while applying an ointment containing honeysuckle to the lesions. At times he cauterized the ulcers using garlic. To complete recovery, he gave a further decoction, which in addition to the ingredients used in the "four rulers" contained rehmannia root, peony root, chinese angelica and szechwan lovage rhizome. This remedy is still in use in Chinese medicine as a tonic for qi and blood.

Chen Sicheng, who lived about 100 years after Wang Ji, devoted an entire work to the treatment of syphilis. His Secret Writings on Putrid Ulcers (mei chuang mi lu) published in 1632 was the first of its kind in China. The book suggested different stages of syphilis symptoms, and prescribing arsenic and mercury to cure syphilis. This preceded their use in Western medicine by about three hundred years. The book also mentioned about how to prevent the problem.

Promotion of Acupuncture

Acupuncture and moxabustion continued to be widely used and studied under the Ming. In 1443, the Ming government ordered to recast a bronze statue marked with the acupuncture points after the one produced in the Song dynasty. Yang Jizhou (1522∼1620) published the most significant treatise of the period on acupuncture, the Great Compendium of Acupuncture and Moxibustion (zheng jiu da cheng). The book not only recorded his own experiences, but also gathered important information from previous texts, discussions covered meridians, aup-points, needling techniques, indications for acupuncture and moxibution, as well as successful and failed case studies. It also introduced integrated experiences on acupuncture application along with drug treatment. The book enjoyed much popularity within the medical community and was regularly reprinted in subsequent centuries.

Pharmacopoeias and Prescription Books

Compendium of Materia Medica was translated into different languages.

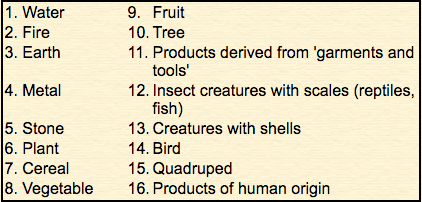

Compendium of Materia Medica was translated into different languages.Classification in the Compendium of Materia Medica differed from previous materia medica by listing drugs under 16 headings:

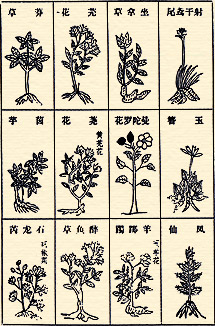

These headings were further subdivided. Plants were organized under their habitat or special character and to some extent Li anticipated the concept of a "plant family." Previous materia medica had been organized by toxicity or by the somewhat arbitrary origins of substances.

Li was also a well-respected physician and maintained a critical approach in his work. He believed that the mind had an important influence on the body. He was the first in China to identify gallstones. He used ice to reduce fever and developed techniques of disinfection. He attached greater attention in his work to the prevention of illness rather than to its cure. By the end of his career, he had a reputation as a herbalist, pharmacologist and physician, and also as a botanist, zoologist and mineralogist. He was a great humanitarian, promoting the Confucian principle that care should be extended to everyone.

Prescription Monographs

Chinese medicine continued to rely mostly on the medical classics and many Ming handbooks drew on these. Standards for the combination, pharmacology, efficacy and administration of herbal prescription were improved during the time of the Ming. Many texts were published, including in 1406 the largest ancient Chinese prescription book, the Universal Aid Formulary (pu ji fang). Zhu Su, Teng Shuo and others compiled this book, listing 61,739 prescriptions with 239 illustrations. They gathered a wide variety of prescriptions and folk remedies, preserving most of the previous records of herbal use for future generations.